The New Canon focuses on

great works of fiction

published since 1985. These

books represent the finest

literature of the current era,

and are gaining recognition as

the new classics of our time. In

this installment of The New

Canon, Ted Gioia reviews The

Things They Carried by Tim

O'Brien.

great works of fiction

published since 1985. These

books represent the finest

literature of the current era,

and are gaining recognition as

the new classics of our time. In

this installment of The New

Canon, Ted Gioia reviews The

Things They Carried by Tim

O'Brien.

The Things They Carried

by Tim O'Brien

Reviewed by Ted Gioia

The story of a war must be a large story, no? From the Iliad to

War and Peace, from Wings to Apocalypse Now, those who

have tried to present a coherent narrative of armed conflict

have invariably found their accounts

bursting at the seams. And even after

the final page, we are frequently left

with the uneasy sense that only a small

microcosm of reality has managed to

step forth from the battlefield and

testify. So much remains mute, buried,

forgotten.

And the Vietnam War, which respected

no boundaries—whether in Southeast

Asia or back on the home front—

presents special challenges to the

teller of tales. Where do you draw

the line? The Tet Offensive? The genocide in Cambodia? The

Kent State shootings? The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to

Henry Kissinger? The military action on the ground provides

just the opening spiral in the widening concentric circles that

still twist and turn, in varying ways, even today. Put bluntly, a

book that tries to grapple with ‘Nam is unlikely to be a

compact one.

Unless its author is Tim O’Brien. The Things They Carried

belongs on any short list of great war fiction, and is one of the

most compelling books yet written about the Vietnam

experience. Yet O’Brien has given us the exact opposite of War

and Peace. And I’m not simply talking about the length of the

work (a scant 233 pages). The very substance of this book

operates on a micro-scale. On the second page, O’Brien even

offers up a list:

….P-38 can openers, pocket knives, heat tabs, wristwatches,

dog tags, mosquito repellent, chewing gum, candy,

cigarettes, salt tablets, packets of Kool-Aid, lighters, matches,

sewing kits, Military Payment Certificates, C rations, and two

or three canteens of water.

In many instances, the items are small enough to fit into a

pocket. And for good reason—because O’Brien is describing

the little things the soldiers brought with them on their

missions. Often O’Brien specifies the weight, since everything

here has a price—and one that is measured more in ounces

carried than dollars spent. This litany of the little, which takes

up the opening 25 pages of The Things They Carried, could

serve as a case study for wannabe writers on the

disproportionate power of the telling detail in narrative fiction.

This book breaks the rules of war fiction in many other ways.

For a battlefield book, there is little actual combat, but this too

enhances the verisimilitude. Recalling his own war

experiences, O’Brien has related that he saw only one enemy

soldier during the course of an entire year. But death is ever

present even when it can’t be assigned to a specific opposing

individual. Flashes of gunfire from hidden places, land mines

and other impersonal dangers can prove no less fatal than a

flesh-and-blood assailant. It is one of the defining

characteristics of this book that its most memorable combat

death comes when a character, the gentle Native American

soldier Kiowa, sinks into the muck of a sewage field in the

midst of a mortar attack. O’Brien emphasizes the almost anti-

heroic nature of the death in a follow-up story that recounts

the nausea-inducing efforts to recover the soldier’s body, and

the consternation of the commanding officer who needs to

draft a letter to Kiowa’s father, but wants to skip over the

unsavory details of the cesspool where his son met his fate.

Tim O’Brien is both the author and a character in this work.

The author as character is a familiar post-modern ploy, and

usually imparts a sense of playful experimentalism to the

proceedings. Paul Auster relies on this device in The New York

Trilogy; Philip Roth does the same in Operation Shylock. And

Martin Amis remarks that when a character named Martin

Amis showed up in his wickedly funny novel Money, the

author’s father (the equally brilliant writer Kingsley Amis)

stopped reading the book and hurled it across the room. That

was breaking the rules of fiction, and just wasn't cricket,

according to the older scribe. Yet there is nothing subversive

or fanciful about O’Brien acting out a role in his own book. For

once, the realism and intensity of the underlying narrative are

reinforced by the authorial intervention, and nothing could

seem like less of a gimmick than the writer actually being there

when ugly things start happening.

As these remarks no doubt make clear, The Things They

Carried does not fall easily into the typical pigeonholes. It is

not memoir, although it has many of the qualities of

autobiography. It is not quite a novel, although the same

characters and themes reappear in the different stories that

constitute the book. It is hardly non-fiction, although it comes

across as a reenactment of real historical events. The author

mixes in shifts of chronology and geography that further

disrupt the narrative flow. Yet these exceptions to familiar

formulas all work to further the power of the finished product.

If anything, The Things They Carried will remind you less of

other war books or movies, but rather will bring to mind the

actual Vietnam vets you may have encountered in your life.

Imagine you have just settled down next to a troubled former

soldier at the local bar, and after a few drinks he decides to tell

you the real inside stuff about what went down in Southeast

Asia—a little rambling perhaps, and likely to focus on the small

things instead of geopolitics, but intensely vivid and

believable. That is the genre at work here—it is the kind of

story that reminds you of the people you’ve met, not the other

stories you have read. And Tim O’Brien’s success at this, the

toughest genre of all, is why his slender book still stands out as

a classic of war fiction a half-century after the American

troops carried their small things off to Vietnam.

by Tim O'Brien

Reviewed by Ted Gioia

The story of a war must be a large story, no? From the Iliad to

War and Peace, from Wings to Apocalypse Now, those who

have tried to present a coherent narrative of armed conflict

have invariably found their accounts

bursting at the seams. And even after

the final page, we are frequently left

with the uneasy sense that only a small

microcosm of reality has managed to

step forth from the battlefield and

testify. So much remains mute, buried,

forgotten.

And the Vietnam War, which respected

no boundaries—whether in Southeast

Asia or back on the home front—

presents special challenges to the

teller of tales. Where do you draw

the line? The Tet Offensive? The genocide in Cambodia? The

Kent State shootings? The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to

Henry Kissinger? The military action on the ground provides

just the opening spiral in the widening concentric circles that

still twist and turn, in varying ways, even today. Put bluntly, a

book that tries to grapple with ‘Nam is unlikely to be a

compact one.

Unless its author is Tim O’Brien. The Things They Carried

belongs on any short list of great war fiction, and is one of the

most compelling books yet written about the Vietnam

experience. Yet O’Brien has given us the exact opposite of War

and Peace. And I’m not simply talking about the length of the

work (a scant 233 pages). The very substance of this book

operates on a micro-scale. On the second page, O’Brien even

offers up a list:

….P-38 can openers, pocket knives, heat tabs, wristwatches,

dog tags, mosquito repellent, chewing gum, candy,

cigarettes, salt tablets, packets of Kool-Aid, lighters, matches,

sewing kits, Military Payment Certificates, C rations, and two

or three canteens of water.

In many instances, the items are small enough to fit into a

pocket. And for good reason—because O’Brien is describing

the little things the soldiers brought with them on their

missions. Often O’Brien specifies the weight, since everything

here has a price—and one that is measured more in ounces

carried than dollars spent. This litany of the little, which takes

up the opening 25 pages of The Things They Carried, could

serve as a case study for wannabe writers on the

disproportionate power of the telling detail in narrative fiction.

This book breaks the rules of war fiction in many other ways.

For a battlefield book, there is little actual combat, but this too

enhances the verisimilitude. Recalling his own war

experiences, O’Brien has related that he saw only one enemy

soldier during the course of an entire year. But death is ever

present even when it can’t be assigned to a specific opposing

individual. Flashes of gunfire from hidden places, land mines

and other impersonal dangers can prove no less fatal than a

flesh-and-blood assailant. It is one of the defining

characteristics of this book that its most memorable combat

death comes when a character, the gentle Native American

soldier Kiowa, sinks into the muck of a sewage field in the

midst of a mortar attack. O’Brien emphasizes the almost anti-

heroic nature of the death in a follow-up story that recounts

the nausea-inducing efforts to recover the soldier’s body, and

the consternation of the commanding officer who needs to

draft a letter to Kiowa’s father, but wants to skip over the

unsavory details of the cesspool where his son met his fate.

Tim O’Brien is both the author and a character in this work.

The author as character is a familiar post-modern ploy, and

usually imparts a sense of playful experimentalism to the

proceedings. Paul Auster relies on this device in The New York

Trilogy; Philip Roth does the same in Operation Shylock. And

Martin Amis remarks that when a character named Martin

Amis showed up in his wickedly funny novel Money, the

author’s father (the equally brilliant writer Kingsley Amis)

stopped reading the book and hurled it across the room. That

was breaking the rules of fiction, and just wasn't cricket,

according to the older scribe. Yet there is nothing subversive

or fanciful about O’Brien acting out a role in his own book. For

once, the realism and intensity of the underlying narrative are

reinforced by the authorial intervention, and nothing could

seem like less of a gimmick than the writer actually being there

when ugly things start happening.

As these remarks no doubt make clear, The Things They

Carried does not fall easily into the typical pigeonholes. It is

not memoir, although it has many of the qualities of

autobiography. It is not quite a novel, although the same

characters and themes reappear in the different stories that

constitute the book. It is hardly non-fiction, although it comes

across as a reenactment of real historical events. The author

mixes in shifts of chronology and geography that further

disrupt the narrative flow. Yet these exceptions to familiar

formulas all work to further the power of the finished product.

If anything, The Things They Carried will remind you less of

other war books or movies, but rather will bring to mind the

actual Vietnam vets you may have encountered in your life.

Imagine you have just settled down next to a troubled former

soldier at the local bar, and after a few drinks he decides to tell

you the real inside stuff about what went down in Southeast

Asia—a little rambling perhaps, and likely to focus on the small

things instead of geopolitics, but intensely vivid and

believable. That is the genre at work here—it is the kind of

story that reminds you of the people you’ve met, not the other

stories you have read. And Tim O’Brien’s success at this, the

toughest genre of all, is why his slender book still stands out as

a classic of war fiction a half-century after the American

troops carried their small things off to Vietnam.

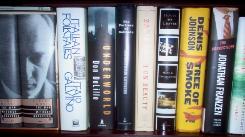

| The New Canon |

| The Best in Fiction Since 1985 |

The New Canon

Home Page

Gabriel García Márquez:

Love in the Time of Cholera

David Foster Wallace:

Infinite Jest

Margaret Atwood:

The Handmaid's Tale

Toni Morrison:

Beloved

Jonathan Franzen:

The Corrections

Don DeLillo:

Underworld

Zadie Smith:

White Teeth

Roberto Bolaño:

2666

Mark Z. Danielewski:

House of Leaves

Cormac McCarthy:

Blood Meridian

Philip Roth:

American Pastoral

Jonathan Lethem:

The Fortress of S0litude

Haruki Murakami:

Kafka on the Shore

Edward P. Jones:

The Known World

Ian McEwan:

Atonement

Michael Chabon:

The Amazing Adventures of

Kavalier & Clay

Philip Roth:

The Human Stain

Mario Vargas Llosa:

The Feast of the Goat

Marilynne Robinson:

Gilead

David Mitchell:

Cloud Atlas

José Saramago:

Blindness

Jennifer Egan:

A Visit from the Good Sqad

W. G. Sebald:

Austerlitz

Jeffrey Eugenides

The Marriage Plot

Donna Tartt:

The Secret History

Michael Ondaatje:

The English Patient

Saul Bellow:

Ravelstein

A.S. Byatt:

Possession

Umberto Eco:

Foucault's Pendulum

Cormac McCarthy:

The Road

David Foster Wallace:

The Pale King

J.K. Rowling:

Harry Potter and the

Sorcerer's Stone

Arundhati Roy:

The God of Small Things

Roberto Bolaño:

The Savage Detectives

Paul Auster:

The New York Trilogy

Per Petterson:

Out Stealing Horses

Ann Patchett:

Bel Canto

Ben Okri:

The Famished Road

Joseph O'Neill:

Netherland

Haruki Murakami:

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Marisha Pessl:

Special Topics in Calamity

Physics

Jonathan Franzen:

Freedom

Colm Tóibín:

The Master

Denis Johnson:

Tree of Smoke

Richard Russo:

Empire Falls

Alice Munro:

Runaway

Martin Amis:

London Fields

Mark Haddon:

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-Time

John Banville:

The Sea

Chuck Palahniuk

Fight Club

Jeffrey Eugenides:

Middlesex

Junot Diaz:

The Brief Wondrous Life of

Oscar Wao

Aravind Adiga:

The White Tiger

Tim O'Brien:

The Things They Carried

Irvine Welsh

Trainspotting

Tobias Wolff:

Old School

Tim Winton:

Cloudstreet

David Foster Wallace:

Oblivion

Oscar Hijuelos:

The Mambo Kings Play

Songs of Love

More to come

Recommended Links:

Great Books Guide

Conceptual Fiction

Postmodern Mystery

Fractious Fiction

Ted Gioia's personal web site

Ted Gioia on Twitter

American Fiction Notes

LA Review of Books

The Big Read

Critical Mass

The Elegant Variation

Dana Gioia

The Literary Saloon

The Millions

The Misread City

Page-Turner

Page Views

Disclosure note: Writers on this site and its

sister sites may receive promotional copies of

works under review.

Home Page

Gabriel García Márquez:

Love in the Time of Cholera

David Foster Wallace:

Infinite Jest

Margaret Atwood:

The Handmaid's Tale

Toni Morrison:

Beloved

Jonathan Franzen:

The Corrections

Don DeLillo:

Underworld

Zadie Smith:

White Teeth

Roberto Bolaño:

2666

Mark Z. Danielewski:

House of Leaves

Cormac McCarthy:

Blood Meridian

Philip Roth:

American Pastoral

Jonathan Lethem:

The Fortress of S0litude

Haruki Murakami:

Kafka on the Shore

Edward P. Jones:

The Known World

Ian McEwan:

Atonement

Michael Chabon:

The Amazing Adventures of

Kavalier & Clay

Philip Roth:

The Human Stain

Mario Vargas Llosa:

The Feast of the Goat

Marilynne Robinson:

Gilead

David Mitchell:

Cloud Atlas

José Saramago:

Blindness

Jennifer Egan:

A Visit from the Good Sqad

W. G. Sebald:

Austerlitz

Jeffrey Eugenides

The Marriage Plot

Donna Tartt:

The Secret History

Michael Ondaatje:

The English Patient

Saul Bellow:

Ravelstein

A.S. Byatt:

Possession

Umberto Eco:

Foucault's Pendulum

Cormac McCarthy:

The Road

David Foster Wallace:

The Pale King

J.K. Rowling:

Harry Potter and the

Sorcerer's Stone

Arundhati Roy:

The God of Small Things

Roberto Bolaño:

The Savage Detectives

Paul Auster:

The New York Trilogy

Per Petterson:

Out Stealing Horses

Ann Patchett:

Bel Canto

Ben Okri:

The Famished Road

Joseph O'Neill:

Netherland

Haruki Murakami:

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Marisha Pessl:

Special Topics in Calamity

Physics

Jonathan Franzen:

Freedom

Colm Tóibín:

The Master

Denis Johnson:

Tree of Smoke

Richard Russo:

Empire Falls

Alice Munro:

Runaway

Martin Amis:

London Fields

Mark Haddon:

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-Time

John Banville:

The Sea

Chuck Palahniuk

Fight Club

Jeffrey Eugenides:

Middlesex

Junot Diaz:

The Brief Wondrous Life of

Oscar Wao

Aravind Adiga:

The White Tiger

Tim O'Brien:

The Things They Carried

Irvine Welsh

Trainspotting

Tobias Wolff:

Old School

Tim Winton:

Cloudstreet

David Foster Wallace:

Oblivion

Oscar Hijuelos:

The Mambo Kings Play

Songs of Love

More to come

Recommended Links:

Great Books Guide

Conceptual Fiction

Postmodern Mystery

Fractious Fiction

Ted Gioia's personal web site

Ted Gioia on Twitter

American Fiction Notes

LA Review of Books

The Big Read

Critical Mass

The Elegant Variation

Dana Gioia

The Literary Saloon

The Millions

The Misread City

Page-Turner

Page Views

Disclosure note: Writers on this site and its

sister sites may receive promotional copies of

works under review.